Set against the backdrop of the 1960s Beat movement in New York, Elise’s is a painful, poetic story of suffering and suicide.

Even if unfamiliar with their work, you’ve likely heard of the Beatniks. Less likely, however, is a familiarity with Elise, and the role she played within this period of literary history. Elise Nada Cowen was a young female graduate, who suffered with mental health issues and was consequently institutionalised by her parents. Despite being a prolific poet, she struggled to see value in her work, and chose to keep her writing private. She has been largely excluded by literary scholars, remembered only as the typist of Beat superstar Allen Ginsberg, or as his experiment in heterosexuality. Following their romance, they both moved onto homosexual relationships, but Elise reportedly remained totally infatuated with the male poet until her suicide at the age of 27. The Beat Generation was famously male-dominated, with many homosexual and bisexual members who were instrumental in the liberalisation of publishing censorship in the United States. The overlooked role of women within the movement is already a point of debate and contention within certain circles. With gender equality generally in the current global consciousness, the emergence of Brenda Callis’ stage production ‘Elise’ still feels relevant, approaching 60 years after the fact.

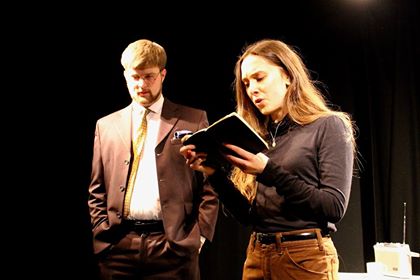

With Permission: Dixie Fried Theatre

The performance began in pitch blackness with ceremonious match lighting. As The Alma Tavern Theatre stage lights rose and the real characters depicted by the five-strong cast were revealed, the reality of the events on which ‘Elise’ is set pierced through the dramatics of the opening scene. Through their brief encounters with each other, recorded readings of Elise’s formerly private collection of surviving poems, and, predominantly, speech delivered directly to the audience, the story of Elise’s life is built up by the Dixie Fried Theatre company’s ensemble cast.

With Permission: Dixie Fried Theatre

A fragmented and often contradictory portrait of the titular character is painted in the words of her former friends and lovers, within the sombre framework of an organised interview, following her death. Through flashbacks, the audience is afforded snapshots of the hedonistic party scene that the poets of the Beat generation were famous for. As author Leo Skir, Guy Woods stood out for his continually captivating portrayal of the Beat sensibility, whilst the rest of the small ensemble cast did well in filling the stage with life and energy during these particular scenes, creating a stark contrast to the sober discourses that dominated the running time (half an hour longer than advertised in my case).

With Permission: Dixie Fried Theatre

Within the performance, no character more loudly seeks justice for Elise, who is herself surprisingly absent, than her close friend Joyce Johnson. A writer herself, the real Johnson published ‘Minor Characters: A Beat Memoir’ in the 1980s, which discusses the forgotten role of women and is a likely source for much of the play’s content. With this rich resource informing the script, the play’s Joyce unsurprisingly offers the most insight into Elise’s character. The extremely dialogue-heavy performance is filled with monologues, and although at times the plot ceases progression, Amelia Paltridge’s Joyce never failed to stir emotion. Her guilt and despair were palpable, and her flawless American accent withstood her voice breaking in grief.

With Permission: Dixie Fried Theatre

Repeatedly hearing how enigmatic and captivating Elise was through the naturally biased account of her guilt-ridden friend, her absence becomes almost distracting. Perhaps it is the intention – a sort of punishment for history’s parallel treatment of her – but still it seems a shame. On the other hand, the professor with whom she had a relationship (so well-played by Harry Petty that his seemingly sprayed grey hair is quickly overlooked!) is a central, recurring character, who tells a rather negative version of Elise’s story. In this role, the professor becomes another man, alongside Allen Ginsberg, by whom she is eclipsed. Similarly her father, briefly portrayed by the same actor that plays Ginsberg (an interesting comment if intentional), has an aggressive presence, bursting on stage, whereas her mother is reduced to a short voice recording.

Named for a principal female contributor within the male-dominated Beat Generation, ‘Elise’ took an incredibly interesting and overlooked part of American literary history and successfully offered it to the public consciousness. The small Alma Tavern Theatre was packed with an enthusiastic and responsive audience, but the plot remained within the sphere of comfortable re-telling. The dramatic artistry of the opening scene set a standard that resurfaced in flashes (the floor strewn with burnt fragments of Elise’s cremated poems, recorded readings of her work in that effortlessly alluring jazzy Beat poet cadence), and that could have been explored further with great success. Instead, the performance was dialogue driven, but at times lacked a navigator. There was no particular direction, revelation, or conclusion; the characters were gathered in reflection rather than action.

With Permission: Dixie Fried Theatre

Whilst excluding Elise as a present character in the performance highlighted her absence from popular Beat history, it felt like a missed opportunity to give her work the attention it lacked during her lifetime. Though enjoyable as it was, a sequel in which Elise is given the space to rebuild herself would be a welcome post-modern reimagining of her history; unfortunately this time, the clearly talented young Dixie Fried Theatre company missed the beat.

Hannah is the regional editor of The State of the Arts in Bristol. Every month she selects one ‘Well Lit’ literary event for review. In May, an important and well-acted play about a forgotten poet ultimately missed the beat.

Filed under: Theatre & Dance, Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: allen ginsberg, Alma Tavern Theatre, Beat poets, Biographical, Dixie Fried Theatre, Elise Cowen, performance, play, poetry, The Alma Tavern, the Beat Generation, theatre

Comments