William Eggleston Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery

August 12, 2016

Eggleston’s Untitled, 1974, Karen Chatham, left, with the artist’s cousin Lesa Aldridge, in Memphis, Tennessee. © Eggleston Artistic Trust

Recently described by the Independent as “the godfather of colour photography”, William Eggleston’s oeuvre is vast, and spans roughly half a century. One hundred portraits by a man who isn’t even known for his portraiture therefore seems marginal in the grand scheme of things, yet this exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery really benefits from being of such a size. Like much of the American’s work, beauty and depth can be found in the modest and the simple, and the lucidity of the show consequently does well to reflect this.

Though it is a common misconception that Eggleston was the very first colour photographer to exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art (in 1976 – he was beaten to it by Ernst Haas ten years before), he is nonetheless rightly credited with bringing the medium to the artistic mainstream. He was a pioneer of the dye-transfer printing method which enabled the rich colour saturation which came to characterise his work, and led the likes of David Lynch to a similar aesthetic.

Untitled, c1975 (Marcia Hare in Memphis Tennessee) by William Eggleston. © Eggleston Artistic Trust

This deep saturation is thus a feature of the exhibition. A photograph of Marcia Hare (above), the seeing of which Sofia Coppola cites as the first time she experienced the feeling of ‘having your breath taken away’, is a prime example. The focus lies solely on the camera and the girl’s face, everything else a blur. This, combined with the trademark depth of ultra-vivid colour provides the eye with an appealing and compelling path across the piece. Until recently, many speculated about the identity of the girl, wondering, in part due to this particular line of focus, whether she was important to the photographer. What was his clear fascination with the subject? Now the National Portrait Gallery has put names to characters, and we begin to get to know Marcia, and by extension the artist for whom she was a sometime muse that little bit better.

Untitled, 1970-4 (Dennis Hopper) by William Eggleston. © Eggleston Artistic Trust

Another star attraction is a photo of Dennis Hopper, director and star of the cult classic Easy Rider. He is shown driving through the outback in the early 1970’s, the desert through the window an unfocused blur, little more than an atmosphere. Meanwhile, the heavy darkness of the interior versus the streak of sunlight shining onto the driver is what makes the image. This sort of suggestiveness through colour is another trait of Eggleston’s. Rather than guiding the viewer to the visually obvious, we can learn a lot from the seemingly routine paraphernalia within the image. In this case, a streak of sunlight through the windscreen tells us just as much about what is going on outside the car as the image of the desert. We are led to pay attention to the dark vs light of the dials, the steering wheel and the silhouettes far more than the spectacle of the landscape, or indeed Hopper himself.

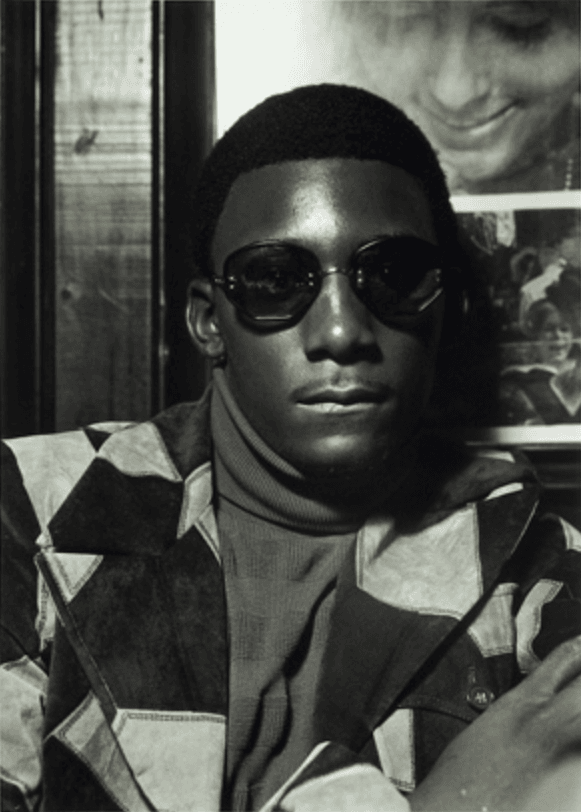

Untitled 1973-4 from ‘Nightclub Portraits Series’ by William Eggleston. © Eggleston Artistic Trust

The show no doubt bounces off these and other well-known, idiomatic Eggleston images. However, it illustrates another side of his work, too, through, among others, a selection of black and whites called the Nightclub Portraits series. A large but simple portrait of a man in sunglasses (above) gives the viewer a sense of looking deep into his eyes. And yet, they’re barely visible. This stands among other images of attractive young subjects from the early seventies which could just as easily be shots from a modelling agency as spontaneous snapshots of a moment in time. And here is where the essence of the photographer’s style shines through in even this exhibition, which is not particularly characteristic of the man whose best-known work is a photograph of a red ceiling. There is very little posing and posturing, just people being people in front of the lens, rendering the time, the place, and the feeling that comes with them just as important as the subjects themselves.

The exhibition runs until 21st October at the National Portrait Gallery. Follow Alex on twitter at @alexmdaniel.

Comments